Show code cell content

try:

import tinygp

except ImportError:

%pip install -q tinygp

try:

import jaxopt

except ImportError:

%pip install -q jaxopt

Getting Started#

Note

This tutorial will introduce some of the basic usage of tinygp, but since we’re going to be leaning pretty heavily on jax, it might be useful to also take a look at the jax docs for some more basic introduction to jax programming patterns.

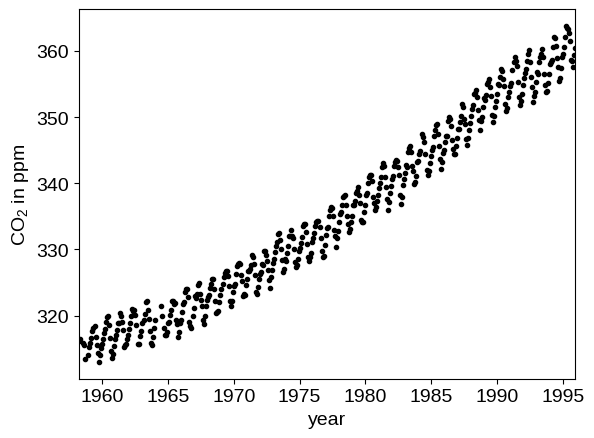

In the following, we’ll reproduce the analysis for Figure 5.6 in Chapter 5 of Rasmussen & Williams (R&W). The data are measurements of the atmospheric CO2 concentration made at Mauna Loa, Hawaii (Keeling & Whorf 2004). The dataset is said to be available online but I couldn’t seem to download it from the original source. Luckily the statsmodels package includes a copy that we can load as follows:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from statsmodels.datasets import co2

data = co2.load_pandas().data

t = 2000 + (np.array(data.index.to_julian_date()) - 2451545.0) / 365.25

y = np.array(data.co2)

m = np.isfinite(t) & np.isfinite(y) & (t < 1996)

t, y = t[m][::4], y[m][::4]

plt.plot(t, y, ".k")

plt.xlim(t.min(), t.max())

plt.xlabel("year")

_ = plt.ylabel("CO$_2$ in ppm")

In this figure, you can see that there is periodic (or quasi-periodic) signal with a year-long period superimposed on a long term trend. We will follow R&W and model these effects non-parametrically using a complicated covariance function. The covariance function that we’ll use is:

where

We can implement this kernel in tinygp as follows (we’ll use the R&W results as the hyperparameters for now):

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from tinygp import kernels, GaussianProcess

jax.config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)

def build_gp(theta, X):

# We want most of our parameters to be positive so we take the `exp` here

# Note that we're using `jnp` instead of `np`

amps = jnp.exp(theta["log_amps"])

scales = jnp.exp(theta["log_scales"])

# Construct the kernel by multiplying and adding `Kernel` objects

k1 = amps[0] * kernels.ExpSquared(scales[0])

k2 = (

amps[1]

* kernels.ExpSquared(scales[1])

* kernels.ExpSineSquared(

scale=jnp.exp(theta["log_period"]),

gamma=jnp.exp(theta["log_gamma"]),

)

)

k3 = amps[2] * kernels.RationalQuadratic(

alpha=jnp.exp(theta["log_alpha"]), scale=scales[2]

)

k4 = amps[3] * kernels.ExpSquared(scales[3])

kernel = k1 + k2 + k3 + k4

return GaussianProcess(

kernel, X, diag=jnp.exp(theta["log_diag"]), mean=theta["mean"]

)

def neg_log_likelihood(theta, X, y):

gp = build_gp(theta, X)

return -gp.log_probability(y)

theta_init = {

"mean": np.float64(340.0),

"log_diag": np.log(0.19),

"log_amps": np.log([66.0, 2.4, 0.66, 0.18]),

"log_scales": np.log([67.0, 90.0, 0.78, 1.6]),

"log_period": np.float64(0.0),

"log_gamma": np.log(4.3),

"log_alpha": np.log(1.2),

}

# `jax` can be used to differentiate functions, and also note that we're calling

# `jax.jit` for the best performance.

obj = jax.jit(jax.value_and_grad(neg_log_likelihood))

print(f"Initial negative log likelihood: {obj(theta_init, t, y)[0]}")

print(

f"Gradient of the negative log likelihood, wrt the parameters:\n{obj(theta_init, t, y)[1]}"

)

Initial negative log likelihood: 392.9423118570187

Gradient of the negative log likelihood, wrt the parameters:

{'log_alpha': Array(3.3025811, dtype=float64), 'log_amps': Array([-56.37950097, 1.71669126, 4.11084749, -2.13098285], dtype=float64), 'log_diag': Array(60.28268107, dtype=float64), 'log_gamma': Array(12.52278878, dtype=float64), 'log_period': Array(2339.70173767, dtype=float64), 'log_scales': Array([117.65693454, -3.10865356, -27.13290445, -4.04980878], dtype=float64), 'mean': Array(-0.15787706, dtype=float64)}

Some things to note here:

If you’re new to

jaxthe way that I’m mixingnpandjnp(thejaxversion ofnumpy) might seem a little confusing. In this example, I’m using regularnumpyto simulate and prepare our test dataset, and then usingjax.numpyeverywhere else. The important point is that within theneg_log_likelihoodfunction (and all the functions it calls),npis never used.This pattern of writing a

build_gpfunction is a pretty common workflow in these docs. It’s useful to have a way of instantiating our GP model at a new set of parameters, as we’ll see below when we plot the conditional model. This might seem a little strange if you’re coming from other libraries (likegeorge, for example), but if youjitthe function (see below) each model evaluation won’t actually instantiate all these classes so you don’t need to worry about performance implications. Check out Modeling Frameworks for some alternative workflows.Make sure that you remember to wrap your function in

jax.jit. Thejaxdocs have more details about how this works, but for our purposes, the key thing is that this allows us to use the expressivetinygpkernel building syntax without worrying about the performance costs of all of these allocations.

Using our loss function defined above, we’ll run a gradient based optimization routine from jaxopt to fit this model as follows:

import jaxopt

solver = jaxopt.ScipyMinimize(fun=neg_log_likelihood)

soln = solver.run(theta_init, X=t, y=y)

print(f"Final negative log likelihood: {soln.state.fun_val}")

Final negative log likelihood: 296.59832193005946

Warning: An optimization code something like this should work on most problems but the results can be very sensitive to your choice of initialization and algorithm. If the results are nonsense, try choosing a better initial guess or try a different value of the method parameter in jaxopt.ScipyMinimize.

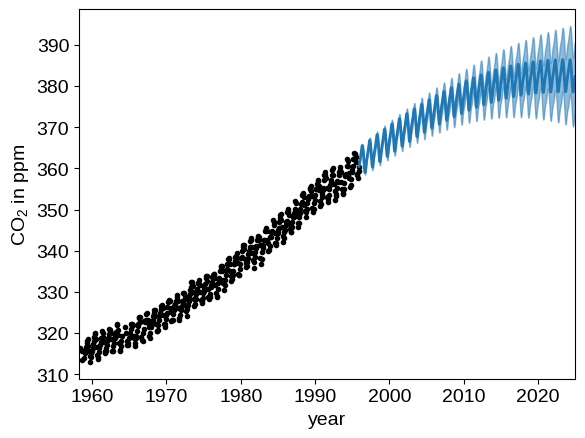

We can plot our prediction of the CO2 concentration into the future using our optimized Gaussian process model by running:

x = np.linspace(max(t), 2025, 2000)

gp = build_gp(soln.params, t)

cond_gp = gp.condition(y, x).gp

mu, var = cond_gp.loc, cond_gp.variance

plt.plot(t, y, ".k")

plt.fill_between(x, mu + np.sqrt(var), mu - np.sqrt(var), color="C0", alpha=0.5)

plt.plot(x, mu, color="C0", lw=2)

plt.xlim(t.min(), 2025)

plt.xlabel("year")

_ = plt.ylabel("CO$_2$ in ppm")